Pachamama depictions were burned as part of a rite of expiation.

(Rome) The Pachamama scandal, which Pope Francis not only tolerated in the context of the Amazon Synod, but actively supported, continues to draw more attention - although largely hushed up by the secular media. Three current examples: the courageous Catholic who disposed of the idols in the Tiber revealed himself; Cardinal Gerhard Müller rejected the attempts to justify the showing of the Pachamama figures; In Mexico, Pachamama replicas were publicly burned as part of a rite of expiation.

An Austrian Pro-Lifer

The Austrian life protector Alexander Tschugguel (for all not in the know: pronounced Tschuggúal, in this Tyrolean family name, the ue Diphthong is pronounced ua) was identified as the main organizer of that action, on the 21st of October in Rome, the Pachamama representations were removed from the church of Santa Maria in Traspontina and disposed of in the Tiber. Tschugguel also organized the recent march for life in Vienna. Kath.net conducted an interview with him, which had explained "that it is something that clearly contradicts Catholic doctrine." When he saw the rituals in the Vatican Gardens, he had the idea of putting an end to the spectacle and making a journey to Rome. For disposal in the Tiber the young activist said:

"I wanted to make sure that these idols are no longer used in church and for church purposes. So, symbolically, it seemed best to throw them into the Tiber.”

The Pro-Lifer Alexander Tschugguel

Pope Francis had not only tolerated the showing of the pagan goddess Pachamama, but supported it in the Vatican Gardens by his presence, and by his explicit presence in St. Peter's, and finally, just before the end of the synod, by his declaration to the synods. He told the synod fathers of the rescue of the figures by the Carabinieri and apologized to "all" who felt insulted by the action. The pope did not apologize for the erection of a pagan idol in St. Peter's Basilica and in the church of Santa Maria in Traspontina and for bishops bringing the statue into the Synod's Hall in procession. There was no question of asking God for forgiveness anyway..

Tschugguel rejects the criticism of his action. She had addressed neither the Amazon Indians nor against the Pope:

"It was all about making this visible violation of the first commandment impossible. It is also successful! At the closing ceremony of the Synod the statues were not there. "

Only now does he confess to the action, because otherwise during the synod everything would have been focused on the persons involved and not on the signal and the message of the action.

Pope Francis with Pachamama in the Vatican Gardens

"We plan to stand up for these beliefs in the future, but we do not see it as our task to do activism.

Nevertheless, we wanted to give the action a face, because we do not want to hide. It is important that people again understand the teaching of Christ our Lord. Then they can face the problems of the world in a sovereign way. When the Church changes the teaching in favor of the zeitgeist, the faithful lose their hold. "

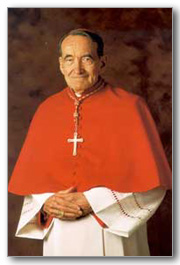

A German cardinal

Cardinal Gerhard Müller, who criticized early on the passing of the pagan idol repeated his criticism in a sermon in Denver in the State of Colorado (USA). There he attended a priestly meeting last week, where Cardinal Raymond Burke was also present. The priest Brian Harrison wrote a memoir of the sermon published by LifeSiteNews.

The former faith prefect of the Church found clear words on the recent events in Rome. The first criticism was the Vatican's lukewarm reaction to the latest column by Eugenio Scalfari in the daily La Repubblica. In it the Masonry atheist claimed that Pope Francis had confirmed to him that although Jesus had been a "great man", he had not been the Son of God. The Vatican had denied it, but that happened in a weak way. Cardinal Muller recalled the words of the Apostle Peter, the first Pope, who

said to Jesus:

"You are Christ, the Son of the living God."

Cardinal Müller had harsh words against the Pachamama spectacle

Accordingly, a clearer reaction from the Vatican would have been needed to dispel any doubt. It would have been necessary to repeat the confession of Peter, and not from the mouth of a media spokesman, but from the mouth of the successor of Peter himself.

Cardinal Müller found clear words against the Pachamama spectacle

The Cardinal also condemned the cult-like Pachamama rituals that had "nothing to do with a true inculturation" with sharp words. Rather, what happened in Rome was a return to pagan myths rather than a cleansing of Indio culture in the light of the message of Christ. As Christianity slowly spread in Roman and Greek culture, according to Cardinal Müller, it was endeavoring "not to preserve or revive the worship of pagan deities of the ancient pantheon". Nor did it try to mix it with the Catholic cult in any way. Referring to the Encyclical Fides et Ratio of Pope John Paul II, the Cardinal said that Christianity had adopted the best elements of civilization, but only for the one purpose of better explaining and promoting the revelation of God in Christ.

A Mexican canon

In Mexico City, Pachamama images were burnt last Sunday in front of a central church in the presence of the rector Hugo Valdemar and an exorcism was prayed. By offering atonement, God was asked to forgive for the sacrileges that were "committed in Rome" in the previous weeks, as stated in the report of a believer present which was published by InfoVaticana.

A month ago, hardly anyone knew the idol Pachamama outside of some Indio groups and neo-Norse circles. Through the organizers of the Catholic Amazon Synod, it became known worldwide. Hugo Valdemar is a canon at the Cathedral of the Archdiocese of Mexico City. He and the faithful gathered for the expiation thought that the Pachamama figures in the Vatican Gardens could make their first appearance in the presence of Pope Francis on the feast day of St. Francis of Assisi. The idols in Rome triggered a polemic, not least among Protestant free churches, who accuse Catholics of "idolatry" whose end is not yet foreseeable.

Canon Hugo Valdemar

Not a few Catholics were irritated and annoyed by the attempt of synod organizers and the Vatican media to deny or disguise the pagan presence and idolatrous background of Pachamama activism. In Latin America, you know exactly what you are talking about, because every day the Church is fighting against forms of idolatry and superstition.

Pachamama Burn in Mexico City

Canon Valdemar was 15 years under Cardinal Norberto Rivera spokesman for the Archdiocese of Mexico City. He is one of the most famous priests in Mexico. Above all, he is an excellent connoisseur of the pre-Christian, pagan religions of Central America and knows about the great

efforts of the missionaries, especially the Franciscans, to eliminate idolatry without any ifs or buts.

Last Sunday, the canon referred to Our Lady of Guadalupe. It is "like a great exorcism, which protects America from idolatry and prepares the way to meet Her Son Jesus Christ.” Many believers have called out to Heaven in recent days because of the confusion publicly and privately.

It is "unbearable" what happened with these "crazy things" in the month of October in Rome and was also experienced remotely by Catholics in America and Mexico, the report says:

"We have the impression that we are experiencing a kind of collective obsession that drives people crazy and darkens their consciousness."

The expiration through the burning of the pachamama figures was for the actions that took place during the Amazon Synod in Rome, but also for the Pachamama prayer of the Italian Episcopal Conference and the Pachamama songs in the Cathedral of Lima. As for Mexico City, Pope Francis also installed a new archbishop in Lima to initiate a change of course for the local church.

In Mexico City, three depictions of Pachamama were burned. Canon Valdemar expressed the hope that the atonement and action might be a model for others. God does not tolerate frivolous dealings with His things, let alone as regards idolatry that violates the First Commandment.

Text: Giuseppe Nardi

Image: InfoVaticana / Nuova Bussola Quotidiana / Youtube (Screenshots)

Trans: Tancred vekron99@hotmail.com

AMDG

[1] Thanks to my colleague Martha Burger for the hint.

Among the major nations of the Western world, the United States is singular in still having the death penalty. After a five-year moratorium, from 1972 to 1977, capital punishment was reinstated in the United States courts. Objections to the practice have come from many quarters, including the American Catholic bishops, who have rather consistently opposed the death penalty. The National Conference of Catholic Bishops in 1980 published a predominantly negative statement on capital punishment, approved by a majority vote of those present though not by the required two-thirds majority of the entire conference.{1} Pope John Paul II has at various times expressed his opposition to the practice, as have other Catholic leaders in Europe.

Among the major nations of the Western world, the United States is singular in still having the death penalty. After a five-year moratorium, from 1972 to 1977, capital punishment was reinstated in the United States courts. Objections to the practice have come from many quarters, including the American Catholic bishops, who have rather consistently opposed the death penalty. The National Conference of Catholic Bishops in 1980 published a predominantly negative statement on capital punishment, approved by a majority vote of those present though not by the required two-thirds majority of the entire conference.{1} Pope John Paul II has at various times expressed his opposition to the practice, as have other Catholic leaders in Europe.

Some Catholics, going beyond the bishops and the Pope, maintain that the death penalty, like abortion and euthanasia, is a violation of the right to life and an unauthorized usurpation by human beings of God's sole lordship over life and death. Did not the Declaration of Independence, they ask, describe the right to life as "unalienable"?

While sociological and legal questions inevitably impinge upon any such reflection, I am here addressing the subject as a theologian. At this level the question has to be answered primarily in terms of revelation, as it comes to us through Scripture and tradition, interpreted with the guidance of the ecclesiastical magisterium.

In the Old Testament the Mosaic Law specifies no less than thirty-six capital offenses calling for execution by stoning, burning, decapitation, or strangulation. Included in the list are idolatry, magic, blasphemy, violation of the sabbath, murder, adultery, bestiality, pederasty, and incest. The death penalty was considered especially fitting as a punishment for murder since in his covenant with Noah God had laid down the principle, "Whoever sheds the blood of man, by man shall his blood be shed, for God made man in His own image" (Genesis 9:6). In many cases God is portrayed as deservedly punishing culprits with death, as happened to Korah, Dathan, and Abiram (Numbers 16). In other cases individuals such as Daniel and Mordecai are God's agents in bringing a just death upon guilty persons.

In the New Testament the right of the State to put criminals to death seems to be taken for granted. Jesus himself refrains from using violence. He rebukes his disciples for wishing to call down fire from heaven to punish the Samaritans for their lack of hospitality (Luke 9:55). Later he admonishes Peter to put his sword in the scabbard rather than resist arrest (Matthew 26:52). At no point, however, does Jesus deny that the State has authority to exact capital punishment. In his debates with the Pharisees, Jesus cites with approval the apparently harsh commandment, "He who speaks evil of father or mother, let him surely die" (Matthew 15:4; Mark 7:10, referring to Exodus 2l:17; cf. Leviticus 20:9). When Pilate calls attention to his authority to crucify him, Jesus points out that Pilate's power comes to him from above that is to say, from God (John 19:11). Jesus commends the good thief on the cross next to him, who has admitted that he and his fellow thief are receiving the due reward of their deeds (Luke 23:41).

The early Christians evidently had nothing against the death penalty. They approve of the divine punishment meted out to Ananias and Sapphira when they are rebuked by Peter for their fraudulent action (Acts 5:1-11). The Letter to the Hebrews makes an argument from the fact that "a man who has violated the law of Moses dies without mercy at the testimony of two or three witnesses" (10:28). Paul repeatedly refers to the connection between sin and death. He writes to the Romans, with an apparent reference to the death penalty, that the magistrate who holds authority "does not bear the sword in vain; for he is the servant of God to execute His wrath on the wrongdoer" (Romans 13:4). No passage in the New Testament disapproves of the death penalty.

Turning to Christian tradition, we may note that the Fathers and Doctors of the Church are virtually unanimous in their support for capital punishment, even though some of them such as St. Ambrose exhort members of the clergy not to pronounce capital sentences or serve as executioners. To answer the objection that the first commandment forbids killing, St. Augustine writes in The City of God:

The same divine law which forbids the killing of a human being allows certain exceptions, as when God authorizes killing by a general law or when He gives an explicit commission to an individual for a limited time. Since the agent of authority is but a sword in the hand, and is not responsible for the killing, it is in no way contrary to the commandment, "Thou shalt not kill" to wage war at God's bidding, or for the representatives of the State's authority to put criminals to death, according to law or the rule of rational justice.

In the Middle Ages a number of canonists teach that ecclesiastical courts should refrain from the death penalty and that civil courts should impose it only for major crimes. But leading canonists and theologians assert the right of civil courts to pronounce the death penalty for very grave offenses such as murder and treason. Thomas Aquinas and Duns Scotus invoke the authority of Scripture and patristic tradition, and give arguments from reason.

Giving magisterial authority to the death penalty, Pope Innocent III required disciples of Peter Waldo seeking reconciliation with the Church to accept the proposition: "The secular power can, without mortal sin, exercise judgment of blood, provided that it punishes with justice, not out of hatred, with prudence, not precipitation." In the high Middle Ages and early modern times the Holy See authorized the Inquisition to turn over heretics to the secular arm for execution. In the Papal States the death penalty was imposed for a variety of offenses. The Roman Catechism, issued in 1566, three years after the end of the Council of Trent, taught that the power of life and death had been entrusted by God to civil authorities and that the use of this power, far from involving the crime of murder, is an act of paramount obedience to the fifth commandment.

In modern times Doctors of the Church such as Robert Bellarmine and Alphonsus Liguori held that certain criminals should be punished by death. Venerable authorities such as Francisco de Vitoria, Thomas More, and Francisco Suárez agreed. John Henry Newman, in a letter to a friend, maintained that the magistrate had the right to bear the sword, and that the Church should sanction its use, in the sense that Moses, Joshua, and Samuel used it against abominable crimes.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century the consensus of Catholic theologians in favor of capital punishment in extreme cases remained solid, as may be seen from approved textbooks and encyclopedia articles of the day. The Vatican City State from 1929 until 1969 had a penal code that included the death penalty for anyone who might attempt to assassinate the pope. Pope Pius XII, in an important allocution to medical experts, declared that it was reserved to the public power to deprive the condemned of the benefit of life in expiation of their crimes.

Summarizing the verdict of Scripture and tradition, we can glean some settled points of doctrine. It is agreed that crime deserves punishment in this life and not only in the next. In addition, it is agreed that the State has authority to administer appropriate punishment to those judged guilty of crimes and that this punishment may, in serious cases, include the sentence of death.

Yet, as we have seen, a rising chorus of voices in the Catholic community has raised objections to capital punishment. Some take the absolutist position that because the right to life is sacred and inviolable, the death penalty is always wrong. The respected Italian Franciscan Gino Concetti, writing in L'Osservatore Romano in 1977, made the following powerful statement:

In light of the word of God, and thus of faith, life all human life is sacred and untouchable. No matter how heinous the crimes . . . [the criminal] does not lose his fundamental right to life, for it is primordial, inviolable, and inalienable, and thus comes under the power of no one whatsoever.If this right and its attributes are so ab solute, it is because of the image which, at creation, God impressed on human nature itself. No force, no violence, no passion can erase or destroy it. By virtue of this divine image, man is a person endowed with dignity and rights.

To warrant this radical revision one might almost say reversal of the Catholic tradition, Father Concetti and others explain that the Church from biblical times until our own day has failed to perceive the true significance of the image of God in man, which implies that even the terrestrial life of each individual person is sacred and inviolable. In past centuries, it is alleged, Jews and Christians failed to think through the consequences of this revealed doctrine. They were caught up in a barbaric culture of violence and in an absolutist theory of political power, both handed down from the ancient world. But in our day, a new recognition of the dignity and inalienable rights of the human person has dawned. Those who recognize the signs of the times will move beyond the outmoded doctrines that the State has a divinely delegated power to kill and that criminals forfeit their fundamental human rights. The teaching on capital punishment must today undergo a dramatic development corresponding to these new insights.

This abolitionist position has a tempting simplicity. But it is not really new. It has been held by sectarian Christians at least since the Middle Ages. Many pacifist groups, such as the Waldensians, the Quakers, the Hutterites, and the Mennonites, have shared this point of view. But, like pacifism itself, this absolutist interpretation of the right to life found no echo at the time among Catholic theologians, who accepted the death penalty as consonant with Scripture, tradition, and the natural law.

The mounting opposition to the death penalty in Europe since the Enlightenment has gone hand in hand with a decline of faith in eternal life. In the nineteenth century the most consistent supporters of capital punishment were the Christian churches, and its most consistent opponents were groups hostile to the churches. When death came to be understood as the ultimate evil rather than as a stage on the way to eternal life, utilitarian philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham found it easy to dismiss capital punishment as "useless annihilation."

Many governments in Europe and elsewhere have eliminated the death penalty in the twentieth century, often against the protests of religious believers. While this change may be viewed as moral progress, it is probably due, in part, to the evaporation of the sense of sin, guilt, and retributive justice, all of which are essential to biblical religion and Catholic faith. The abolition of the death penalty in formerly Christian countries may owe more to secular humanism than to deeper penetration into the gospel.

Arguments from the progress of ethical consciousness have been used to promote a number of alleged human rights that the Catholic Church consistently rejects in the name of Scripture and tradition. The magisterium appeals to these authorities as grounds for repudiating divorce, abortion, homosexual relations, and the ordination of women to the priesthood. If the Church feels herself bound by Scripture and tradition in these other areas, it seems inconsistent for Catholics to proclaim a "moral revolution" on the issue of capital punishment.

The Catholic magisterium does not, and never has, advocated unqualified abolition of the death penalty. I know of no official statement from popes or bishops, whether in the past or in the present, that denies the right of the State to execute offenders at least in certain extreme cases. The United States bishops, in their majority statement on capital punishment, conceded that "Catholic teaching has accepted the principle that the State has the right to take the life of a person guilty of an extremely serious crime." Joseph Cardinal Bernardin, in his famous speech on the "Consistent Ethic of Life" at Fordham in 1983, stated his concurrence with the "classical position" that the State has the right to inflict capital punishment.

Although Cardinal Bernardin advocated what he called a "consistent ethic of life," he made it clear that capital punishment should not be equated with the crimes of abortion, euthanasia, and suicide. Pope John Paul II spoke for the whole Catholic tradition when he proclaimed in Evangelium Vitae (1995) that "the direct and voluntary killing of an innocent human being is always gravely immoral." But he wisely included in that statement the word "innocent." He has never said that every criminal has a right to live nor has he denied that the State has the right in some cases to execute the guilty.

Catholic authorities justify the right of the State to inflict capital punishment on the ground that the State does not act on its own authority but as the agent of God, who is supreme lord of life and death. In so holding they can properly appeal to Scripture. Paul holds that the ruler is God's minister in executing God's wrath against the evildoer (Romans 13:4). Peter admonishes Christians to be subject to emperors and governors, who have been sent by God to punish those who do wrong (1 Peter 2:13). Jesus, as already noted, apparently recognized that Pilate's authority over his life came from God (John 19:11).

Pius XII, in a further clarification of the standard argument, holds that when the State, acting by its ministerial power, uses the death penalty, it does not exercise dominion over human life but only recognizes that the criminal, by a kind of moral suicide, has deprived himself of the right to life. In the Pope's words,

Even when there is question of the execution of a condemned man, the State does not dispose of the individual's right to life. In this case it is reserved to the public power to deprive the condemned person of the enjoyment of life in expiation of his crime when, by his crime, he has already dispossessed himself of his right to life.

In light of all this it seems safe to conclude that the death penalty is not in itself a violation of the right to life. The real issue for Catholics is to determine the circumstances under which that penalty ought to be applied. It is appropriate, I contend, when it is necessary to achieve the purposes of punishment and when it does not have disproportionate evil effects. I say "necessary" because I am of the opinion that killing should be avoided if the purposes of punishment can be obtained by bloodless means.

The purposes of criminal punishment are rather unanimously delineated in the Catholic tradition. Punishment is held to have a variety of ends that may conveniently be reduced to the following four: rehabilitation, defense against the criminal, deterrence, and retribution.

Granted that punishment has these four aims, we may now inquire whether the death penalty is the apt or necessary means to attain them.

Rehabilitation

Capital punishment does not reintegrate the criminal into society; rather, it cuts off any possible rehabilitation. The sentence of death, however, can and sometimes does move the condemned person to repentance and conversion. There is a large body of Christian literature on the value of prayers and pastoral ministry for convicts on death row or on the scaffold. In cases where the criminal seems incapable of being reintegrated into human society, the death penalty may be a way of achieving the criminal's reconciliation with God.

Defense against the criminal

Capital punishment is obviously an effective way of preventing the wrongdoer from committing future crimes and protecting society from him. Whether execution is necessary is another question. One could no doubt imagine an extreme case in which the very fact that a criminal is alive constituted a threat that he might be released or escape and do further harm. But, as John Paul II remarks in Evangelium Vitae, modern improvements in the penal system have made it extremely rare for execution to be the only effective means of defending society against the criminal.

Detterence

Executions, especially where they are painful, humiliating, and public, may create a sense of horror that would prevent others from being tempted to commit similar crimes. But the Fathers of the Church censured spectacles of violence such as those conducted at the Roman Colosseum. Vatican II's Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World explicitly disapproved of mutilation and torture as offensive to human dignity. In our day death is usually administered in private by relatively painless means, such as injections of drugs, and to that extent it may be less effective as a deterrent. Sociological evidence on the deterrent effect of the death penalty as currently practiced is ambiguous, conflicting, and far from probative.

Retribution

In principle, guilt calls for punishment. The graver the offense, the more severe the punishment ought to be. In Holy Scripture, as we have seen, death is regarded as the appropriate punishment for serious transgressions. Thomas Aquinas held that sin calls for the deprivation of some good, such as, in serious cases, the good of temporal or even eternal life. By consenting to the punishment of death, the wrongdoer is placed in a position to expiate his evil deeds and escape punishment in the next life. After noting this, St. Thomas adds that even if the malefactor is not repentant, he is benefited by being prevented from committing more sins. Retribution by the State has its limits because the State, unlike God, enjoys neither omniscience nor omnipotence. According to Christian faith, God "will render to every man according to his works" at the final judgment (Romans 2:6; cf. Matthew 16:27). Retribution by the State can only be a symbolic anticipation of God's perfect justice.

For the symbolism to be authentic, the society must believe in the existence of a transcendent order of justice, which the State has an obligation to protect. This has been true in the past, but in our day the State is generally viewed simply as an instrument of the will of the governed. In this modern perspective, the death penalty expresses not the divine judgment on objective evil but rather the collective anger of the group. The retributive goal of punishment is misconstrued as a self-assertive act of vengeance.

The death penalty, we may conclude, has different values in relation to each of the four ends of punishment. It does not rehabilitate the criminal but may be an occasion for bringing about salutary repentance. It is an effective but rarely, if ever, a necessary means of defending society against the criminal. Whether it serves to deter others from similar crimes is a disputed question, difficult to settle. Its retributive value is impaired by lack of clarity about the role of the State. In general, then, capital punishment has some limited value but its necessity is open to doubt.

There is more to be said. Thoughtful writers have contended that the death penalty, besides being unnecessary and often futile, can also be positively harmful. Four serious objections are commonly mentioned in the literature.

There is, first of all, a possibility that the convict may be innocent. John Stuart Mill, in his well-known defense of capital punishment, considers this to be the most serious objection. In responding, he cautions that the death penalty should not be imposed except in cases where the accused is tried by a trustworthy court and found guilty beyond all shadow of doubt.

It is common knowledge that even when trials are conducted, biased or kangaroo courts can often render unjust convictions. Even in the United States, where serious efforts are made to achieve just verdicts, errors occur, although many of them are corrected by appellate courts. Poorly educated and penniless defendants often lack the means to procure competent legal counsel; witnesses can be suborned or can make honest mistakes about the facts of the case or the identities of persons; evidence can be fabricated or suppressed; and juries can be prejudiced or incompetent. Some "death row" convicts have been exonerated by newly available DNA evidence. Columbia Law School has recently published a powerful report on the percentage of reversible errors in capital sentences from 1973 to 1995. Since it is altogether likely that some innocent persons have been executed, this first objection is a serious one.

Another objection observes that the death penalty often has the effect of whetting an inordinate appetite for revenge rather than satisfying an authentic zeal for justice. By giving in to a perverse spirit of vindictiveness or a morbid attraction to the gruesome, the courts contribute to the degradation of the culture, replicating the worst features of the Roman Empire in its period of decline.

Furthermore, critics say, capital punishment cheapens the value of life. By giving the impression that human beings sometimes have the right to kill, it fosters a casual attitude toward evils such as abortion, suicide, and euthanasia. This was a major point in Cardinal Bernardin's speeches and articles on what he called a "consistent ethic of life." Although this argument may have some validity, its force should not be exaggerated. Many people who are strongly pro-life on issues such as abortion support the death penalty, insisting that there is no inconsistency, since the innocent and the guilty do not have the same rights.

Finally, some hold that the death penalty is incompatible with the teaching of Jesus on forgiveness. This argument is complex at best, since the quoted sayings of Jesus have reference to forgiveness on the part of individual persons who have suffered injury. It is indeed praiseworthy for victims of crime to forgive their debtors, but such personal pardon does not absolve offenders from their obligations in justice. John Paul II points out that "reparation for evil and scandal, compensation for injury, and satisfaction for insult are conditions for forgiveness."

The relationship of the State to the criminal is not the same as that of a victim to an assailant. Governors and judges are responsible for maintaining a just public order. Their primary obligation is toward justice, but under certain conditions they may exercise clemency. In a careful discussion of this matter Pius XII concluded that the State ought not to issue pardons except when it is morally certain that the ends of punishment have been achieved. Under these conditions, requirements of public policy may warrant a partial or full remission of punishment. If clemency were granted to all convicts, the nation's prisons would be instantly emptied, but society would not be well served.

In practice, then, a delicate balance between justice and mercy must be maintained. The State's primary responsibility is for justice, although it may at times temper justice with mercy. The Church rather represents the mercy of God. Showing forth the divine forgiveness that comes from Jesus Christ, the Church is deliberately indulgent toward offenders, but it too must on occasion impose penalties. The Code of Canon Law contains an entire book devoted to crime and punishment. It would be clearly inappropriate for the Church, as a spiritual society, to execute criminals, but the State is a different type of society. It cannot be expected to act as a Church. In a predominantly Christian society, however, the State should be encouraged to lean toward mercy provided that it does not thereby violate the demands of justice.

It is sometimes asked whether a judge or executioner can impose or carry out the death penalty with love. It seems to me quite obvious that such officeholders can carry out their duty without hatred for the criminal, but rather with love, respect, and compassion. In enforcing the law, they may take comfort in believing that death is not the final evil; they may pray and hope that the convict will attain eternal life with God.

The four objections are therefore of different weight. The first of them, dealing with miscarriages of justice, is relatively strong; the second and third, dealing with vindictiveness and with the consistent ethic of life, have some probable force. The fourth objection, dealing with forgiveness, is relatively weak. But taken together, the four may suffice to tip the scale against the use of the death penalty.

The Catholic magisterium in recent years has become increasingly vocal in opposing the practice of capital punishment. Pope John Paul II in Evangelium Vitae declared that "as a result of steady improvements in the organization of the penal system," cases in which the execution of the offender would be absolutely necessary "are very rare, if not practically nonexistent." Again at St. Louis in January 1999 the Pope appealed for a consensus to end the death penalty on the ground that it was "both cruel and unnecessary." The bishops of many countries have spoken to the same effect.

The United States bishops, for their part, had already declared in their majority statement of 1980 that "in the conditions of contemporary American society, the legitimate purposes of punishment do not justify the imposition of the death penalty." Since that time they have repeatedly intervened to ask for clemency in particular cases. Like the Pope, the bishops do not rule out capital punishment altogether, but they say that it is not justifiable as practiced in the United States today.

In coming to this prudential conclusion, the magisterium is not changing the doctrine of the Church. The doctrine remains what it has been: that the State, in principle, has the right to impose the death penalty on persons convicted of very serious crimes. But the classical tradition held that the State should not exercise this right when the evil effects outweigh the good effects. Thus the principle still leaves open the question whether and when the death penalty ought to be applied. The Pope and the bishops, using their prudential judgment, have concluded that in contemporary society, at least in countries like our own, the death penalty ought not to be invoked, because, on balance, it does more harm than good. I personally support this position.

In a brief compass I have touched on numerous and complex problems. To indicate what I have tried to establish, I should like to propose, as a final summary, ten theses that encapsulate the Church's doctrine, as I understand it.

- The purpose of punishment in secular courts is fourfold: the rehabilitation of the criminal, the protection of society from the criminal, the deterrence of other potential criminals, and retributive justice.

- Just retribution, which seeks to establish the right order of things, should not be confused with vindictiveness, which is reprehensible.

- Punishment may and should be administered with respect and love for the person punished.

- The person who does evil may deserve death. According to the biblical accounts, God sometimes administers the penalty himself and sometimes directs others to do so.

- Individuals and private groups may not take it upon themselves to inflict death as a penalty.

- The State has the right, in principle, to inflict capital punishment in cases where there is no doubt about the gravity of the offense and the guilt of the accused.

- The death penalty should not be imposed if the purposes of punishment can be equally well or better achieved by bloodless means, such as imprisonment.

- The sentence of death may be improper if it has serious negative effects on society, such as miscarriages of justice, the increase of vindictiveness, or disrespect for the value of innocent human life.

- Persons who specially represent the Church, such as clergy and religious, in view of their specific vocation, should abstain from pronouncing or executing the sentence of death.

- Catholics, in seeking to form their judgment as to whether the death penalty is to be supported as a general policy, or in a given situation, should be attentive to the guidance of the pope and the bishops. Current Catholic teaching should be understood, as I have sought to understand it, in continuity with Scripture and tradition.

Endnotes:

- The statement was adopted by a vote of 145 to 31, with 41 bishops abstaining, the highest number of abstentions ever recorded. In addition, a number of bishops were absent from the meeting or did not officially abstain. Thus the statement did not receive the two-thirds majority of the entire membership then required for approval of official statements. But no bishop rose to make the point of order.